Research in Action: Anna Majury

Research in Action

12 Jan 2017

Beneath the surface: Probing the dynamics of private well water

One-third of Ontarians (and 98% of rural Ontarians) rely on private well water as their primary drinking water source. Unlike municipal water supplies, private wells are not regulated and well stewardship is the owner’s responsibility. Like any water source, well water can become contaminated with bacteria. The risk goes up during periods of heavy rainfall, or snow melt, such as spring and fall, but multiple, and often unpredictable, factors come in to play.

Understanding the risks for contamination associated with private well water is a key focus for Dr. Anna Majury, a veterinarian and clinical microbiologist overseeing foodborne and waterborne pathogens at Public Health Ontario Laboratories. Using state-of-the-art molecular methods and geospatial techniques, she and her collaborators are shedding new light on private well water quality issues in Ontario.

In a recent study, the team pored over tens of thousands of private well water records for water tested at PHO Laboratories. (Testing for bacterial contamination is provided free of charge to private well owners by PHO.)

“Studying drinking water is a relatively recent venture for me, so I was taken in by the data when I first started to review them. Firstly, I was interested in the fact that, during those years for which we have good data (>10 years), it was clear that the water quality, on an aggregated level, appeared unchanged, with between 5 and 40% of all wells tested showing evidence of bacterial contamination at some level, year after year, and yet this remained uninvestigated, even ten years post-Walkerton. We wanted to look at these data more closely, not just by submissions, but by the actual individual wells themselves, so that we could investigate the possible link between geography and water quality. In so doing, we discovered that there are geographic regions in which the wells have an elevated risk of being contaminated with E. coli, the current standard fecal indicator organism for drinking water monitoring. And, of course, where there are feces, there exists the possibility that pathogens spread via feces, such as norovirus or Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC), are also present,” explains Dr. Majury.

Her team used computer-based mapping technology and other statistical tools to examine over 90,000 quality testing records for distinct wells, from a five-year period in southeastern Ontario and another 120,000 for all of southern Ontario.

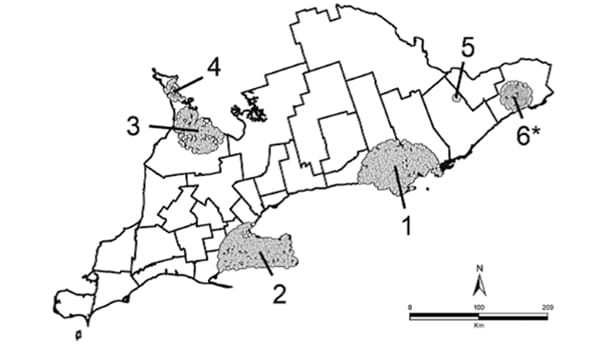

“We discovered four major hotspots where wells were 1.5 to 10 times more likely to be contaminated with E. coli,” says Dr. Majury, principal author of the study, published in the journal Geospatial Health.

Figure 1. Southern Ontario map of clusters at 50% maximum population size. Numbers mark the individual clusters. Clusters 5 and 6, although present, were not significant.

What could explain these hotspots? Dr. Majury thinks there are probably several factors, including local hydrogeology. For example, paleozoic bedrock (limestone) is common in several of the hotspots, particularly along the Great Lakes. Easily fractured, limestone allows contaminants to travel through it with relative ease and over great distances. These regions, likely because of having water access, are also among the first settled in the province, thus, wells, both active and abandoned, are older, and perhaps lack the same integrity as newly constructed wells. Other factors of influence might include land use, septic systems, overburden, population density, and socioeconomic status. Current work in her laboratory examines these and other factors on a geographic level, in an attempt to better align testing guidelines to risk, by region, using geographically weighted regression models. Already, public health units are using these results to target well owners in the hotspot areas and to stress the importance of well water testing.

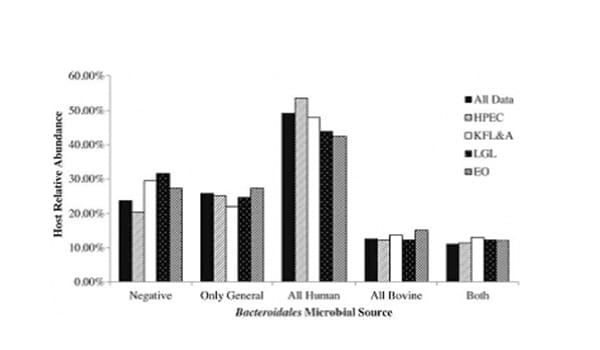

Identifying where the fecal contamination comes from is a priority for Dr. Majury. In a second study, published in the Journal of Water and Health, fecal contamination sources for over 700 E. coli-positive well water samples from southeastern Ontario were analyzed. The results were surprising.

“While cattle are often blamed for fecal contamination, we found that nearly half of the E. coli-contaminated well water samples, in the particular region studied, were contaminated with markers of human fecal contamination, whereas only 13% had evidence of bovine-derived fecal contamination, including 11% that had evidence of both human and bovine feces.”

Figure 2. Distribution of microbial sources overall and geographically stratified by public health unit.

Dr. Majury hypothesizes that other parts of Ontario, where farming practices are more intensive, may potentially show different outcomes. Her next study will identify the source of fecal contamination for drinking water wells in several farm-rich regions.

“If we know whether the well is contaminated by human, bovine, or other animal sources, including wildlife, we can speculate as to what the potential health risks might be to the well water consumer. Moreover, we can direct resources and public health interventions to mitigating the particular risks. For example, if the risk is primarily from human sources, such as via septic tanks, there are measures that can be put in play to help address this, including revisiting the system itself or informing and potentially changing policy.”

One of the greatest barriers to a better understanding of well water quality in the province is the fact well owners submit their waters for testing far too infrequently.

“I think people have good intentions, but our memories are short, and Walkerton was many years ago now,” says Dr. Majury. “Because well owners are not testing, they are not adequately informed about the quality of their water, and may even be consuming fecally contaminated, and possibly disease-causing, water. However, we do little currently to monitor water-related outbreaks or infections, not just in Ontario, but most of Canada. We intend to work towards improving that in future, through both improved testing and the data collected at the time of the test.”

But, changing individual behaviour may not be easy. Historically, PHO recommended testing well water at least three times a year, a minimum of three weeks apart, for bacteria (until three “clean” samples are obtained). However, most private well owners aren’t doing that, according to Dr. Majury’s research. Analyzing five years of well testing data from southeastern Ontario, the PHO team found that only 11–12% of wells met these testing guidelines in any year, and a mere 0.3% met them in every year over a five-year period. These historic guidelines are no longer endorsed by PHO, and the current modelling work mentioned above, is intended to help tailor testing recommendations to the well, based on appropriate risk assessment.

Figure 3. Map of study region showing unique properties separated by the number of years of private well water submissions from each property (1 (red) being one year submitted between 2008 to 2012 to 5 (dark green) being submissions from all 5 years).

With collaborators at PHO, Queen’s University, public health units and others, Dr. Majury brings a rare background to her research. Being both a veterinarian and a clinical microbiologist while working in environmental health, enables a unique perspective, one that is perhaps less intuitive for others.

“I do consider myself a “One Health” practitioner with focus on the human–animal–environmental continuum. My understanding is academic, but also very practical and experienced-based. I like to work on projects that address important health issues from a holistic perspective and that alter practice for the better, in real time.”

Don’t have a MyPHO account? Register Now